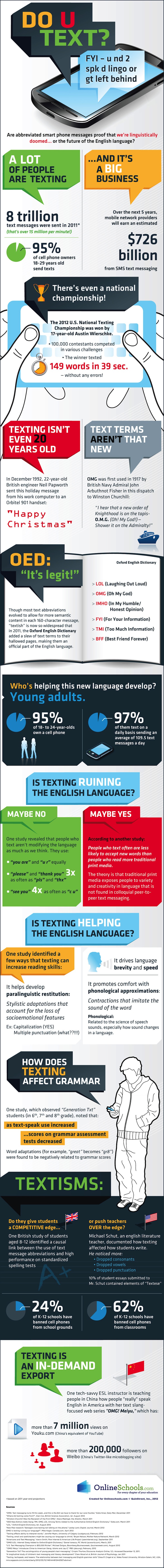

A new infographic shows that texting has had a major effect on the English language in a short amount of time.

Although the technology behind text messaging is less than 20 years old, some studies show that people who text often do not learn or process new words as efficiently as people who engage with print media. Of course, this is somewhat flawed–texters could still read print media–but the idea is that peer-to-peer text messaging exposes users to a limited set of words.

On the other hand, textspeak isn’t as widespread as many people would believe–“u r” and “you are” are used equally often according to one study, and “see you” is used four times as often as “c u.” People don’t seem to limit themselves to “textspeak.”

From a linguistics standpoint, texting has a similarly mixed effect on cognitive development. One study showed that texting develops paralinguistic restitution, which is a way to make text messages seem more socially or emotionally expressive. For instance, texters might use smiley faces, capitalization and heavy punctuation to get certain ideas across. Texting also makes readers more comfortable with misspellings that are similar to the intended word phonologically–for instance, “u r” instead of “you are.”

Perhaps most tellingly, a study showed that as text use increased among school-aged children, grammar scores decreased. This was largely due to the type of phonological word adaptations that texting promotes.

Some linguistics experts argue that these adaptations are actually good for the English language–Professor David Crystal wrote a notable op-ed for the Guardian in which he hargued that “there is increasing evidence that [texting] helps rather than hinders literacy.”

For better or worse, we’re changing our language around texting, and with 8 trillion texts sent worldwide in 2011, the technology and its associated linguistic changes are clearly here to stay.

Infographic By: OnlineSchools.org

Leave a Reply